Adopting Colemak

Last year, I realised my typing accuracy was a source of frustration, especially when programming. I’d picked up typing decades prior and had developed an idiosyncratic technique. I was happy with my speed, but not my consistency, and had to make regular corrections. I also used my right hand to press keys on the left side of the keyboard, so my hands were moving side to side a lot, which got tiring during long sessions.

To fix this, I decided to learn to type “properly”. Since I’d be relearning finger positions anyway, I also decided switched layouts, from QWERTY to something better, as I was aware of alternatives that reduce finger travel and awkward movements.

Choosing a layout

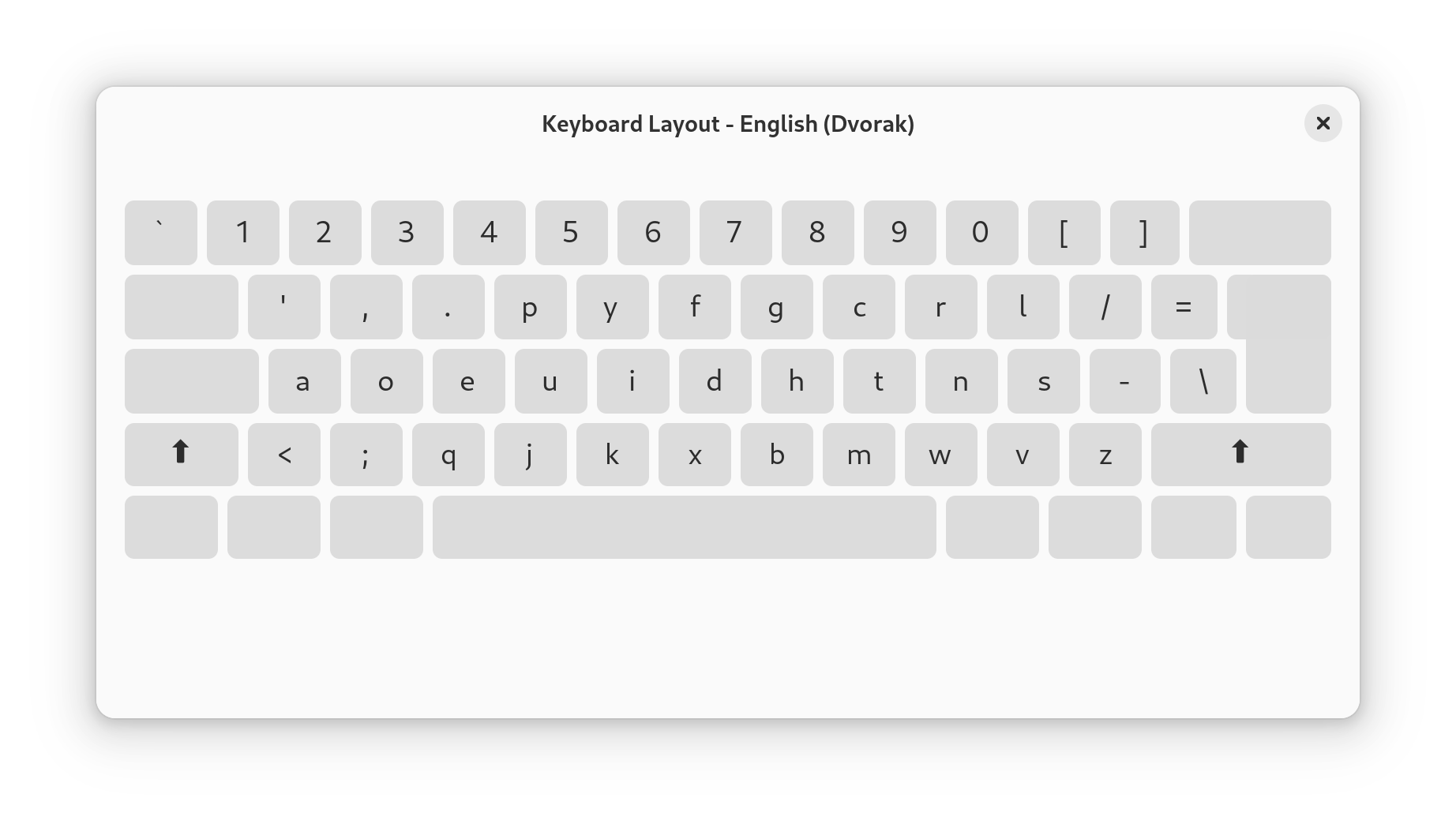

The two most common alternatives to QWERTY are Dvorak and Colemak. Dvorak is the older and more common of the two (though still rare compared to QWERTY), originating in 1936. Dvorak is designed to put the most common letters in English prose on the home row (the middle row of keys on which your fingers rest whilst not typing). The vowels are placed under the left hand, and the most common consonants under the right hand. Dvorak moves many of the non-alphanumeric keys away from their positions in QWERTY, as shown below.

Colemak is more recent, having been developed in 2006. It takes QWERTY as a base and keeps the position of most non-alphanumeric keys, along with the keys used in common shortcuts like undo/copy/paste, as shown below. That makes it easier to pick up than Dvorak, especially as a programmer who types delimiters and punctuation a lot. The remaining alphanumeric keys are distributed so that common letters in English prose are placed on the home row, and frequent letter combinations are typed with alternating hands. It also tries to avoid common letter pairs that would use the same finger twice in a row, which is slow.

Whilst Dvorak and Colemak are the most common alternative keyboard layouts, there’s a long tail of other choices such as Workman and Norman. Although these claim advantages over Dvorak and Colemak, the main benefits of an alternative layout come from having a purposely designed layout that isn’t QWERTY. The efficiency improvements from these other layouts are marginal, and there are other tradeoffs. Only Dvorak and Colemak are supported by the desktop operating systems I use regularly (Linux and macOS) without installing additional software or requiring administrator privileges.

From these two options, I chose Colemak for its closer similarity to QWERTY. It also scores better than Dvorak on the typing effort model developed by the Carpalx project: Colemak requires less effort than Dvorak, whilst making greater use of the home row and balancing keypresses more evenly between your left and right hands.

The learning process

I got proficient with Colemak over a couple of months by spending 30 minutes a day practising. I continued using QWERTY outside these practice sessions, so as not to hinder myself at work whilst getting to a usable speed and accuracy with Colemak.

As mentioned above, my primary goal in changing from QWERTY wasn’t to become a faster typist, but to improve my consistency and reduce fatigue, using all ten fingers and dropping the idiosyncratic habits I’d picked up. To achieve this, I planned my learning in three stages.

At first, I learnt the key placements and finger assignments. I practised key placements and finger assignment using Colemak Club, learning from a reference diagram from the Colemak website. Colemak Club breaks learning the key placements into seven levels, where the first level introduces the eight keys under the fingers on the home row, and once these are learnt, more columns and rows are introduced in each consecutive level until by the final level you’ve learnt the position of every alphabetic key.

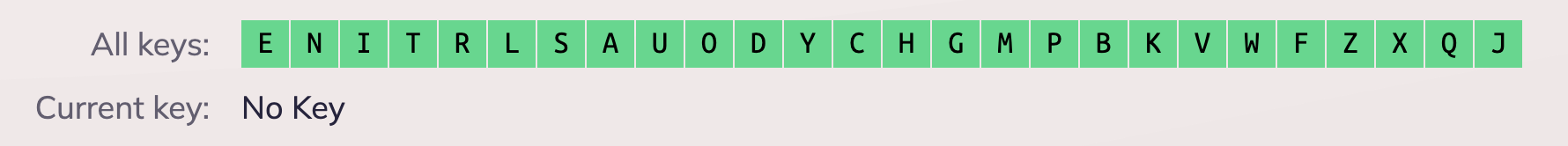

Once I’d learnt key placements and which finger to press each key with, I focused on developing consistency in hitting the correct keys, practising on keybr.com. Keybr.com generates random words to type, initially using only a small subset of the alphabet. Once you’re proficient in typing these keys, additional letters are introduced. Per-key statistics such as accuracy and time to type are calculated, and based on this, new words are generated that oversample the keys that you’re able to type less quickly or accurately. This provides targeted practice to spend more time on the keys you’re least proficient with.

Once you’ve reached a threshold speed and accuracy on every letter, the icons in keybr.com will all be coloured green. I got to this point around one month after starting to learn Colemak. At that point, I dropped QWERTY and switched to Colemak full-time, being fast and accurate enough for tasks such as taking notes during meetings.

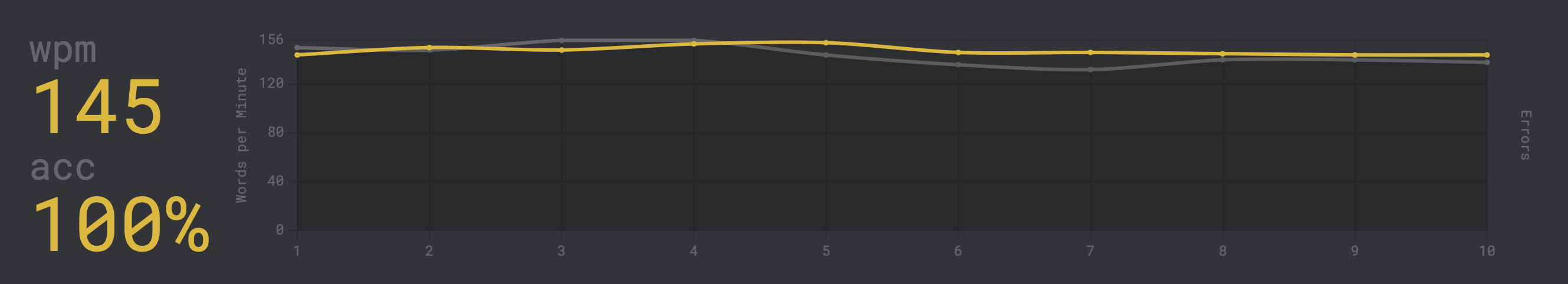

I continued 30 minutes of practice each day, alongside using Colemak the rest of the time. At this point, I wanted to practise typing real English words, to train myself on common n-grams and not just individual letters. For this, I used Monkeytype, which allows setting a minimum accuracy level, below which the session will be marked as failed and have to be repeated. I used this to improve accuracy without chasing speed at the expense of accuracy. After a month of this practice alongside using Colemak full-time, I was happy with where I’d got to and stopped the practice sessions.

Reflections

Looking back a year after I made the switch, I’m happy I hit the goals I set. With daily use after those first two months of practice, my accuracy is better than it was on QWERTY, and I’m faster too: on a good run I can pass 140 words per minute. I use all 10 fingers, have dropped the bad habits developed when I originally learned to type, and my hands move less from side to side.

I’m glad I invested the time in learning and adopting Colemak. If you’re a programmer who spends a lot of time typing but isn’t happy with your accuracy and comfort, it’s worth trying a different layout.